I love it when I’m right, and I especially love it when what proves I’m write is something the kids find all cool and hip like Fortnite. In Chapter 2 of Copyright for Creatives I wrote:

“Choreographic works are only protected if they’re recorded somehow—in choreographic notation, for instance, or video. Just doing a dance doesn’t make it intellectual property (particularly when I do a dance). … However, common movements or activities, like yoga positions, line dances and exercise routines, are not copyrightable, even when they are unique. Individual ballet or dance positions that are commonly used are also not copyrightable, because they’re commonly-used and not unique.”

I go on about this at some further length in Chapter 8 as well.

So imagine my delight when, in Hanagami v Epic Games[1], the court pretty much said exactly the same thing, proving that Copyright for Creatives contains actual, valuable, accurate legal concepts and guidance, and is not just 244 pages of nonsense written by some guy with too much time on his hands.

Here’s what happened in Hanagami. Long ago (way back in 2017, when we were all young, innocent, and unvaccinated against Covid-19), Kyle Hanagami, a professional choreographer, posted a five-minute video on YouTube that showed him and some other dancers performing a dance he’d designed specifically to accompany the Charlie Puth song, “How Long.” Cleverly anticipating the recommendations included in Copyright for Creatives by some three years, Hanagami registered the video with the US Copyright Office—but only those elements of it that showed his dance moves; he obviously had no rights to Puth’s music.

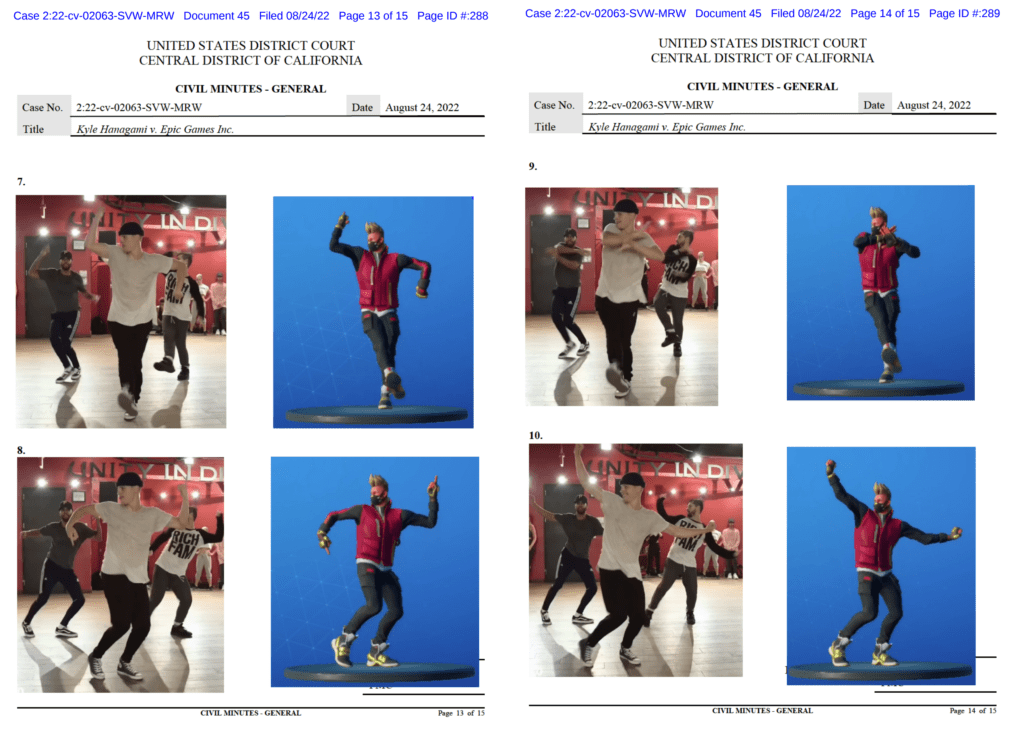

The defendant, Epic Games, produces the video game Fortnite, which the court describes as “a free-to-play multiplayer shooting game where players can explore a virtual world, build and destroy structures, and compete to the last player alive.”[2] Using virtual currency, players can customize the game, purchase supplies, weapons, and costumes for their characters in the “Item Shop.” They can also purchase what are called “emotes”—basically short animations like dances or other movements that their characters can perform in response to events. Hanagami felt that the “It’s Complicated” emote was too similar to his choreography for “How Long” and sued Epic Games for infringement. After reviewing the video and the emote, the court determined that ten of the 96 movements in Hanagami’s choreography were identical to ten of the movements in the emote’s 106 moves, but that only four of the movements were protectable. (Photos from the decision are attached at the end of this post).

However, just because the ten dance moves were the same doesn’t mean there was infringement involved. The court observed that any choreography is simply a combination of established movements in a particular order—much like photography is simply the operation of light on film or a digital translation of light and shadow. The uniqueness, the copyrightability part, comes from a human being making specific decisions with those established tools. In photography, the photographer makes unique decisions about angles and light settings and contrast and focus, and those things make the image protectable, even when the image is of a subject that’s not protected, like a mountain.

In dance, it’s the same thing: a choreographer arranges the dancers’ body movements in a certain order, in a way that’s responsive to music or rhythm. Those individual movements are essentially poses–many of which are long-established and have their own names. Taken individually, a pose is not copyrightable. Blended together in a specific order, though, those poses become choreography, and potentially protectable. However, as discussed in Copyright for Creatives, that arrangement of movements is only copyrightable if it’s in a tangible form: choreographic notation, or a filmed performance. A live, unrecorded, spontaneous dance (like the one I do when Amazon reports a book sale or five-star review) is not copyrightable. Obviously, since Hanagami videoed and posted his dance on YouTube, the choreography can be copyrighted.

In this case, gamers will be pleased to know, the court found in favor of Fortnite. “Here,” wrote the court, “the two works are not substantially similar because other than the four identical counts of poses—which are unprotected alone—[the two works] do not share any creative elements.”[3] The court point out, correctly, that Hanagami’s choreography was set to specific music and performed by human dancers in the real world and recorded for a YouTube audience, while Fortnite’s emote was performed by animated characters in a virtual world for an in-game audience.[4]

As with all things copyrightish, the more unique and original the better: simply stringing together standard dance steps and physical poses may be no more protectable than dancing like nobody’s watching. So the bottom line for choreographers is that copyrighting your work is a tricky, um, dance with copyright law.

[1] Kyle Hanagami v. Epic Games Inc., No. 22-cv-02063-SVW-MRW (C.D. Cal. Aug. 24, 2022) (Dkt. 45)

[2] Id.

[3] Id., page 8

[4] Id.