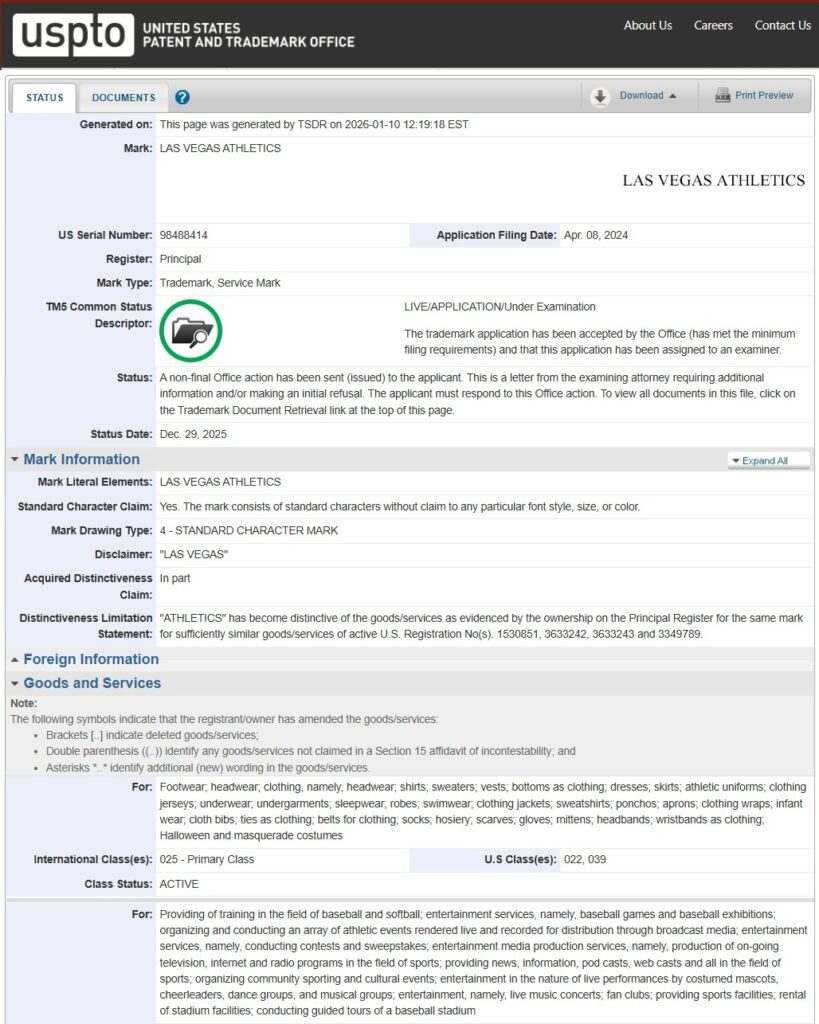

It’s not news that the Athletics baseball team, formerly of Oakland, is relocating to Las Vegas. I live here, and construction on the new stadium for the city’s adopted team is well underway across the street from the MGM Grand and New York New York casinos, at the intersection of Las Vegas Boulevard (“The Strip”) and Tropicana Avenue. What is exciting news—at least to someone obsessed with intellectual property law—is that the US Patent & Copyright Office has denied the Athletics’ application to trademark “Las Vegas Athletics” or “Vegas Athletics” on the grounds that the name is insufficiently unique. [1] In trademark terms, it’s too generic. The USPTO also suggested that the proposed mark could cause consumer confusion: there are no fewer than seven gyms called “Las Vegas Athletic Club” located in the valley where Vegas sits.[2]

So that’s where things stand at the moment. The A’s ownership has the right to appeal the USPTO’s decision, which the USPTO itself characterizes as “[a] non-final Office action … from the examining attorney requiring additional information and/or making an initial refusal.” Basically, the USPTO is inviting the applicant to make a stronger case.

How did the Athletics find themselves in this predicament? Well, let’s consult Copyright for Creatives: A Practical Guide to Copyright Law for Creative People Who Make Stuff, which includes a lengthy appendix discussing the copyright-adjacent issues of trademarks and patents.

To begin with, a trademark is generally a word, phrase, symbol, design, or a combination of those elements, that identifies and distinguishes the goods of one party from those of others.[3] You’re probably familiar with the R and TM symbols: they indicate that a trademark is protected. But they don’t mean the same thing.

TM means “trademarked,” and it applies automatically when a mark is first put to use in the market, giving notice to everyone that you claim this mark, and if they use it you’ll pitch a big fit. But that’s all it means, because the trademark is not necessarily protectible in court unless it’s been registered with the US Patent and Trademark Office. And that’s what the R indicates: The mark has been registered, and if someone uses it they will be sued and the trademark holder will very likely win, because the law provides protections for registered trademarks and punishments for their infringement. In this case, the Athletics aren’t interested in just writing cease-and-desist letters, they want their exclusive right to use the name protectable in court, and enforceable by hefty fines for infringement.

Long ago, a case called Abercrombie & Fitch v. Hunting World[4] established five categories of potential trademarks. In descending order of the likelihood of protection they are:

- Fanciful: composed of invented words.

- Arbitrary: common words, but not connected to their characteristics.

- Suggestive: suggests quality or some other characteristic.

- Descriptive: A term is descriptive if it conveys an immediate idea of the ingredients, qualities or characteristics of the goods.

- Generic: Identifies a product irrespective of its origin. Soap brand soap, for instance, or Computer brand computers. There is no legal protection for generic trademarks.

The USPTO (rightly in my opinion) designated “Las Vegas Athletics” as Generic—that is, not entitled to legal protection by trademark. Think of it this way: Two thirds of the proposed mark are just the name of a city, and you can’t trademark a city’s name—especially a city in which you aren’t currently doing business.[5] The remaining word is “athletics,” which simply defines the players involved, who are—presumably—athletes. Plus there’s already those “Las Vegas Athletic Clubs” scattered around the neighborhood that have no relationship with the baseball team, but that consumers might mistakenly think are somehow affiliated.[6] All in all a pretty clear-cut case of an attempt to trademark common, generic words.

It would be truly unfortunate if individuals were able to trademark generic words in common usage. Way back in 1871, the Supreme Court said “Nor can a generic name, or a name merely descriptive of an article or its qualities, ingredients, or characteristics, be employed as a trademark and … be entitled to legal protection.“[7] That’s good news for people who don’t want to be sued every time they order toast in a diner just because someone’s trademarked “toast.”

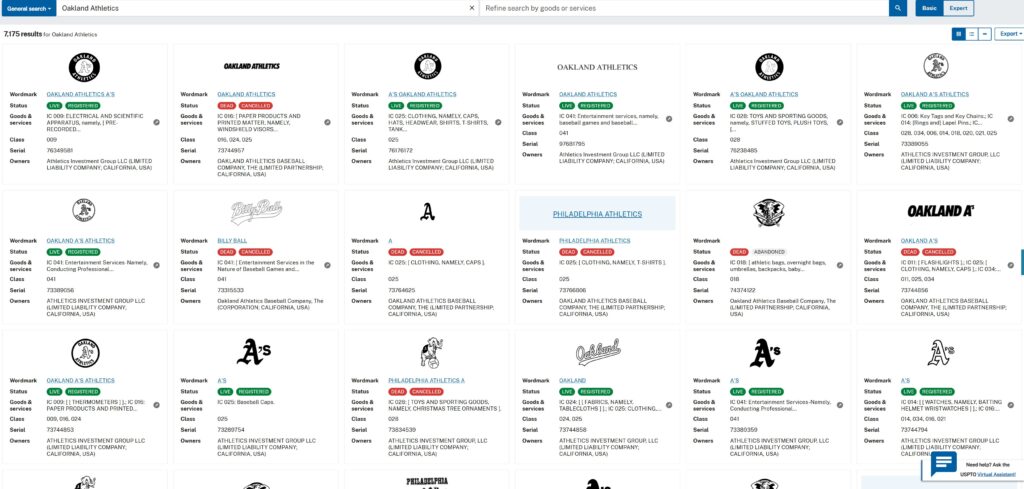

Interestingly, though, previous USPTOs were not so picky about the Athletics: “Oakland Athletics” was successfully trademarked from 1968 to 2024, as were the team’s previous incarnations as the “Philadelphia Athletics” (1901–1954) and “Kansas City Athletics” (1955–1967).

The A’s ownership will most certainly ask for an extension and opportunity to appeal, so there is a significant likelihood that their lawyers will be able to convince the USPTO that the “Las Vegas Athletics” is a protectable mark. It’s realistically very unlikely that a longtime major league baseball team would be denied protectable use of their name. Alternatively, of course, they could just make a large donation to the Trump Ballroom and avoid all the paperwork…

[1] The basic facts about the Oakland application and its rejection are drawn from “Las Vegas A’s trademark denied — is it a ‘big deal’ or ‘workable problem’?”, Howard Stutz (Nevada Independent, January 9th, 2026 (https://thenevadaindependent.com/article/las-vegas-as-trademark-denied-is-it-a-big-deal-or-workable-problem)

[2] In the interests of transparency, I also sit in the same valley as Las Vegas.

[3] https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/basics/what-trademark

[4] Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Hunting World, Inc., 537 F.2d 4 (2d Cir. 1976)

[5] A trademark cannot be “misleading regarding the geographic origin of the goods or services.” 15 U.S. Code § 1052

[6] A trademark cannot resemble another registered mark in a way that would cause consumer confusion. Id.

[7] Delaware & Hudson Canal Company v. Clark, 80 U.S. 311 (1871)